I haven’t done a post specifically about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) for a while now, although that is the perspective from which I approach a lot of the issues I blog about. With that in mind, I thought I’d go back to basics and write a beginner’s guide to MMT as I see it. Any errors that follow will be mine alone. Please let me know if you spot one!

What is MMT? Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a branch of the heterodox Post Keynesian school of economics. At a basic level it is comprised of the following ideas:

- Taxes drive money;

- Taxes and borrowing don’t pay for government spending;

- Countries like the UK cannot go bust;

- Functional finance;

- Sectoral balances;

- Endogenous money;

- Governments should pursue full employment;

- Focus on real resources, not money.

So what do all these things means? In turn then:

1. Taxes drive money In theory, anyone can start their own currency. You or I could just print up some notes in our garage. The trick though is getting it accepted. MMT posits that in order for governments to get its citizens to accept and use their currency, it is sufficient for them to impose a tax in that currency. Provided they are able to enforce the payment of the tax, people will be willing to work for payment in that currency in order to pay the tax. So the necessity to pay the tax in the government’s currency drives demand for that currency and ensures it has a value.

Further reading:

MMP Blog #8: Taxes Drive Money

Tax-driven Money: Additional Evidence from the History of Thought, Economic History, and Economic Policy

2. Taxes and borrowing don’t pay for government spending While governments do need to tax, MMT says that they do not do it to pay for their spending. Indeed, MMTers argue that government spending must come first. How can anyone pay a tax denominated in the government’s currency unless the government first spends it into the economy? So what are taxes for? We have already seen one function of tax in point 1. Taxes drive the nations currency. They also act to ‘make room’ for the governments spending, preventing that spending from generating inflation. Progressive taxes are also used for re distributive purposes to help a government meet it social aims, and taxes can also be effective to incentivise or disincentivise certain behaviours (e.g. smoking, drinking, polluting). But what about government borrowing? At the moment, if the amount of tax collected is less than the amount a government spends, it ‘borrows’ the rest by issuing government bonds. The amount it borrows is repaid with interest. MMT though, argues that similar to taxation, this borrowing is not undertaken to finance its spending, but to maintain its target interest rate. Under current arrangements, if a government didn’t match its spending to taxes plus borrowing, this would create excess reserves in the banking system, and this would drive overnight interest rates down to zero. Government borrowing also acts as a risk-free source of savings to the private sector, including pension funds.

Further reading:

Taxes for revenue are obsolete

Government bonds and interest rate maintenance

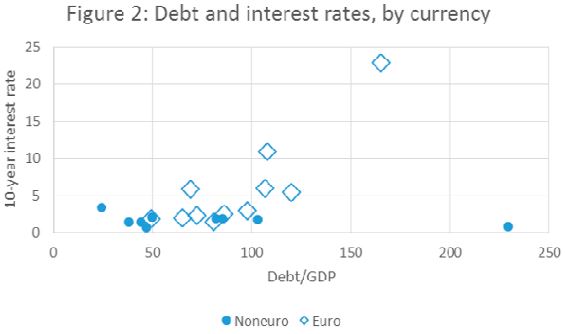

3. Countries like the UK cannot go bust In the run up to the 2010 UK General Election, it was said loudly and often that the UK was on the brink of bankruptcy, about the go the same way as Greece. We had run out of money. MMT says this is nonsense. Governments like the UK who issue their own currency cannot go bust, in the sense that they cannot run out of money. In this sense the UK differs from the Eurozone countries, who, since joining the Euro, no longer issue their own currencies. They are now currency users. This point is often missed when discussing government debts. The usual story is that when ‘the markets’ see government debts rising, they start to worry about how the debt will be repaid and so demand higher rates of interest before they will lend more. This happened in some of the Eurozone counties before the European Central Bank stepped in to stabilise the markets for these countries debt. Countries like the UK though have central banks that can always intervene if interest rates start to rise, so the risk of an interest rate spike here is low to non-existent. Interest rates on government debt are a policy choice for the currency-issuing government. To maintain the maximum flexibility over an economy, MMT recommends countries maintain their own free floating currency, and to only borrow in that currency.

Further reading:

There is no solvency issue for a sovereign government

Why do politician tell us Debt/Deficit myths which they must know to be untrue?

4. Functional Finance Functional finance is an approach to fiscal policy adopted by MMTers but first espoused by economist Abba Lerner. Functional finance has three rules:

- The government shall maintain a reasonable level of demand at all times. If there is too little spending and, thus, excessive unemployment, the government shall reduce taxes or increase its own spending. If there is too much spending, the government shall prevent inflation by reducing its own expenditures or by increasing taxes.

- By borrowing money when it wishes to raise the rate of interest and by lending money or repaying debt when it wishes to lower the rate of interest, the government shall maintain that rate of interest that induces the optimum amount of investment.

- If either of the first two rules conflicts with principles of ‘sound finance’ or of balancing the budget, or of limiting the national debt, so much the worse for these principles. The government press shall print any money that may be needed to carry out rules 1 and 2.

Further reading:

Functional Finance

Functional finance and modern monetary theory

5. Sectoral balances Sectoral balances is an approach to viewing the financial makeup of the macro economy, popularised by economist Wynne Godley. It helps not to view things like the government deficit in isolation, but rather to see it in the context of what’s happening elsewhere in the economy. In the three sector version of Godley’s sectoral balances: Government balance = Private sector balance – Foreign sector balance If we apply this to the UK, we see a government deficit of 6%, a private sector balance (private sector sayings – private sector investment) of 2% and a foreign balance (exports – imports) of -4%. MMTers argue that the natural state for the private sector is surplus, so for countries with trade deficits, a government deficit will also be the norm. If the government tries to reduce or eliminate its deficit, it will only succeed if the private sector is willing to reduce or eliminate its surplus.

Further reading:

What Happens When the Government Tightens its Belt?

UK Sectoral Balances and Private Debt Levels

6. Endogenous Money Endogenous money is the idea that rather than the central bank determining the amount of money in the economy – exogenously, the amount of money is instead determined by the supply and demand of loans. In shorthand, MMTers (and Post Keynesians in general) would say, “Loans create deposits”. That is to say that banks create money by extending loans to customers, while at the same time creating a corresponding deposit. This runs contrary to what is generally taught to students of economics – that savings are loaned out with banks acting purely as intermediaries, or at best leveraging an initial injection of government money by a predetermined ratio.

Further reading:

The Endogenous Money Approach

Money creation in the modern economy

7. Governments should pursue full employment In the post war period up until the early 70s, Western governments were committed to the principle of full employment, and largely achieved this, with the unemployment rate averaging around 3% in the UK throughout that period. The Conservatives famous “Labour Isn’t Working” campaign poster of 1979 was powerful because unemployment had reached previously unthinkable levels of 1 million. Today, the Government start high-fiving each other when unemployment falls below 2.5 million. MMTers argue that achieving full employment again is very much a realistic and achievable goal, but it means abandoning modern notions that “governments don’t create jobs”, and accepting that capitalism left to its own devices will never employ all those willing and able to work. A key tenet of MMT is that governments should act as the ’employer of last resort’, offering work to all those who are willing and able to work, but unable to find a job.

Further reading:

The Job Guarantee: A Government Plan for Full Employment

The job guarantee is a vehicle for progressive change

8. Focus on real resources, not money While politicians tell us there is no money left, millions are without sufficient work and resources lie idle. MMT argues that we should focus on these real things – people and resources – rather than money which is just a tool for putting those people and resources to work. Governments can and should spend money into the economy when the private sector cannot or will not to maximise the potential output of the economy.

Further reading:

Modern Monetary Theory: The Last Progressive Left Standing

Scottish Independence – A Modern Money Analyisis

Those are some of the basics of MMT then, not that I can capture it all in 1,500 words. For more reading, try some of the links on my blogroll.