This post will attempt to explain a concept in economics known as “sectoral balances”. This might get a bit wonkish, but hopefully not too much.

We hear a lot about the Government’s debt and deficit, how it is too high and must be reduced even at the expense of jobs and living standards. What we rarely, if ever hear about though is the other side of the ledger – the private sector. Here’s an example of what I mean:

Here’s a chart of UK Government debt. It’s risen from around 40% of GDP 25 years ago, to a little under 70% in 2012. A pretty big rise huh? But what about private sector debt?*

25 years ago, total private sector debt was just under 150% of GDP, but by the time the 2008/9 crisis hit, this had more than trebled to over 450%. While the debt households and non-financial companies increased significantly over the period (doubling and trebling respectively), the main culprit was the financial sector, who’s debt peaked at 258% of GDP in Q1 2010. Looking at the two charts above, which problem looks more urgent? But yet the focus on the government’s finances is relentless.

Look again at the second chart, and you’ll see that following the crash, all three parts of the private sector started to reduce their debts, although this year that trend seems to have paused. This is what is known as deleveraging – paying down debt. Economists like Richard Koo have labelled this period of deleveraging a “balance sheet recession“. Basically, when asset prices collapse following the bursting of a bubble, millions of private sector entities find themselves in dire straits, so they all simultaneously attempt to increase savings or pay down debt at the same time, causing a collapse in economic activity.

Now back in 2011, David Cameron drew the ire of some economists when a speech he was about to make reportedly contained the lines:

“the only way out of a debt crisis is to deal with your debts. That means households – all of us – paying off the credit card and store card bills”.

Now Cameron’s problem wasn’t the advice per se, (it’s probably a good idea for households in too much debt to cut back) his problem was that he’d forgotten the economics he’d learned while studying PPE at Oxford, namely Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift. While for an individual, saving or paying down debt may be a sensible thing to do, because my spending is your income and vice versa, if everyone tries to do it at the same time, total savings will actually fall. This allows me finally to get to the point of this post.

While the government’s deficit is always discussed, what is never discussed it that the government’s deficit is equal to the surplus of the private sector. The approach of examining changes in the economy by looking at different sectors in the economy is known as the sectoral balances approach, which was popularised by British economist, the late Wynne Godley. It highlights the accounting tautology that shows:

Private Balance = Government Balance + Trade Balance

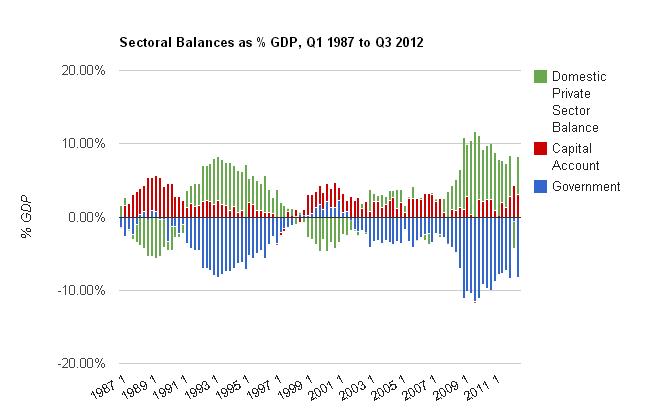

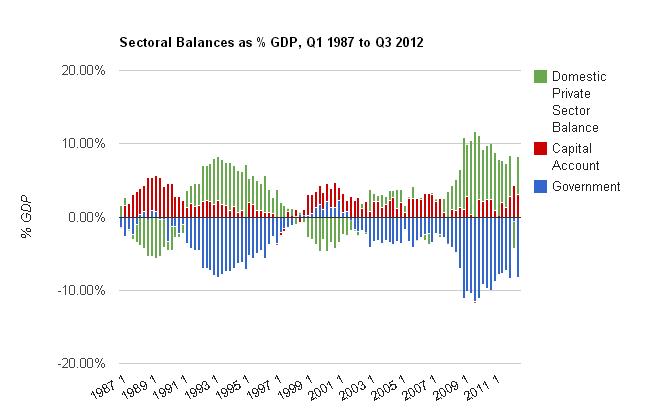

The private balance is private savings minus private investment spending, the government balance is government spending minus tax receipts and the trade balance is exports minus imports. This equation is always true whether there is a government deficit, surplus or balanced budget. Here you can see a graphical representation* by way of illustration using real data for the UK.

In this chart, the red bars represent the capital account which is equal but inverse to the trade balance (or current account to be more precise). This just helps to show more clearly how the governments budget position mirrors the position of the non-government sector. So, in the latest quarter, a 5% private sector surplus and a 3% capital account surplus is offset by an 8% deficit.

The point of showing this is to say that the government cannot really have a budget deficit target and hit it because it depends upon what happens in the other two sectors. When Cameron says he thinks households should pay down debts, he doesn’t realise that its impossible for both the government and the private sector to do that at the same time, unless the country has a very sizable trade surplus (which we certainly don’t have). The government can either accommodate the private sector’s desire to pay down debt/save by increasing spending/cutting taxes, or it can try to cut its own spending and at the same time hope households and businesses will be willing to take on more debt.

In a sane world, the government would realise that the first option is preferable, but instead it has plumped for option 2. If you look at the figures produced by the OBR**, you can actually see that deficit reduction is predicated on households going into deficit again. This cannot be a sensible strategy. The problem the government has is that while it can control some portion of its budget, it can’t control other parts like the welfare bill, and it can’t control how much tax it takes in. These things are determined by saving and investment decisions made by the private sector and the performance of exports over imports. Once this is understood, it’s clear to see how commentators like Fraser Nelson are misguided when they say there are no cuts because spending is going up. The government are making cuts, its just that those cuts are causing other parts of the budget (parts they have no control over) to go up.

The sectoral balances approach then allows us to consider how changes in government policy may impact upon the different sectors. Armed with this knowledge you would know that for the government deficit to go down, the private surplus and/or the trade deficit would need to shrink or disappear entirely. At a time of global recession, the prospects for a massively shrinking trade deficit don’t seem good, and the prospects for an already debt-saturated private sector to take on yet more debt also seem less than positive. Both of these things imply that any attempt to reduce the government’s deficit by cutting spending or raising taxes will ultimately be futile, and that’s exactly what we are seeing at the moment.

Here then are the key take away point from this post:

- Outstanding private debt dwarfs government debt, both as a % of GDP and in the extent to which it is a problem that needs dealing with.

- Considering the government deficit in isolation leads to wrong-headed policy making. Policy-making should take account of all sectors of the economy when considering the implications of different policy options.

- The three sectors must balance. In a trade deficit nation like the UK, if the private sector is saving/paying down debt, a government deficit is inevitable regardless of the government’s spending plans. Any attempt by the government to cut it’s deficit will fail unless the private sector is willing to cut its surplus/run a deficit.

- Those who argue austerity is not happening do not understand the points above and don’t get the ‘tyranny of the accounting’.

* The second and third charts in this post have been taken from this excellent blog. The blog’s author Neil Wilson updates these charts on a quarterly basis as new data is published. Here is the post the charts are taken from.

** The OBR publishes forecasts for what they think will happen to the sectoral balances (they call them financial balances) here (Its the supplementary fiscal tables, tab 1.8).